Imagine entire Roman legions vanishing in the East, only for some of those Romans to reappear later in China.

Follow me on this journey to explore the mystery of the forgotten “Chinese Romans”.

Let’s start this story backwards, as we are unfolding this thread. There is a region in modern north-west China with 'European-looking' villagers, having fair hair and green/blue eyes; this strange phenomenon has an appeal in itself that perpetuates the mystery around their origin and history.

It is reported that DNA tests have shown the residents in a village called Gansu are the blond-haired, blue-eyed descendants of Roman legionnaires who ended up there almost 2,000 years ago. One theory is that these Romans were settled in a border town called Liqian, a name some scholars believe could be a transliteration of "legion."

The town, located on the fringes of the Han Empire, was strategically important and would have benefited from the defensive skills of the Roman soldiers. But how did they end up there?

Time to go further back in time, to the beginning of this mystery, and see how the end of a Roman general inspired the Game of Thrones scene with someone being drowned in molten gold. The Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE was a devastating defeat for the Roman Republic, marking one of the worst military disasters in Roman history. Crassus, one of Rome’s wealthiest and most ambitious leaders, led a force of about 40,000 men into Parthia, modern-day Iran.

Just to set the setting, we are talking about the times of the Triumvirate in Rome; a political alliance between Ceasar (yes that one), Pompey and Crassus. As we have discussed in previous threads, political power in Rome came with military glory; Cesar was doing great, like Pompey, but Crassus was just a very wealthy man. He needed his own victories. And since Pompey was in the West, Cesar in the Nort, he could only go one way: East.

The entire Eastern campaign resulted from the need for the glory of Crassus, who wanted to match in war fame the other triumvirs. The mysterious Parthian Empire, which controlled part of the Silk Road and trade between the Mediterranean world and India, influenced the imagination of Crassus, who had wet dreams about easy Roman conquests.

He had much money but obviously no military experience or prudence; he hastily assembled legions creating an army of 40.000 men. He marched East and entered the treacherous desert regions of Persia. His route led him across the Euphrates River and into the desert, an area unfamiliar to the Romans and poorly suited for their traditional style of warfare.

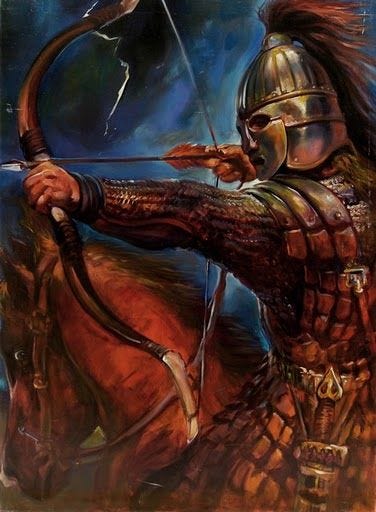

The campaign culminated in the Battle of Carrhae, near the town of Harran in modern-day Turkey. Here, Crassus faced the Parthian general Surena, who commanded a smaller but highly mobile force of cavalry, including the feared cataphracts (heavily armored cavalry) and horse archers. The Parthians employed hit-and-run tactics, using their superior mobility to keep the Romans at bay and showering them with arrows.

Crassus, unprepared for this style of warfare, struggled to respond effectively. The Roman infantry, weighed down by heavy armor and equipment, found themselves surrounded and harassed by the relentless Parthian cavalry. Despite several attempts to break the Parthian lines, the Romans were unable to engage the enemy in close combat, where their strength lay.

The battle was a catastrophe for the Romans. Crassus’ forces were decimated, with thousands fallen and many more captured. Crassus himself was lured into a parley under the pretense of negotiation, where he was treacherously terminated—an event that became infamous for the humiliating end of a Roman general.

According to one account, molten gold was poured into Crassus' mouth, symbolizing his insatiable greed. They kept the golden head as a trophy, Remember the scene from Game of Thrones where the arrogant Viserys Targaryen is drowned in molten gold by Khal Drogo?

The defeat at Carrhae was one of Rome’s worst military disasters, comparable to the losses at Cannae against Hannibal. The Parthians took thousands of prisoners, and the Roman standards, symbols of Rome's military honor, were captured—a loss that was deeply humiliating to the Roman people.

According to historical records, about 10,000 Roman soldiers were captured. While the fate of these prisoners is largely unknown, one enduring legend suggests that a contingent of these soldiers eventually made their way to China, where they settled and left a lasting legacy.

Following their defeat, the surviving Roman soldiers were taken prisoner by the Parthians. Some were integrated into the Parthian military, while others were relocated to the eastern borders of the Parthian Empire, far from their homeland. The Parthians, recognizing the strategic advantage of these experienced soldiers, may have used them to garrison their eastern frontier against the nomadic tribes that threatened their borders.

According to Plutarch and Pliny the Elder, some settled in Margiana (a land in Central Asia, close to the Chinese state) in the eastern part of the Parthian empire to guard the borders against the invasion of steppe nomads. This was not the first time these regions were seeing a Mediterranean civilization, as the Greeks had reached it and settled there after Alexander’s campaigns.

The legend suggests that a group of Romans, either as prisoners or mercenaries, were eventually relocated further east. Over time, these soldiers may have escaped or been released and continued their journey eastward. They would have traversed the rugged terrain of the Central Asian steppes, crossing vast deserts and high mountains, encountering various tribes and cultures along the way.

This journey could have taken several years, during which the Romans adapted to their new environments, adopting local customs and possibly even forming alliances with local tribes. Their Roman military discipline and skills would have made them valuable allies or formidable enemies, ensuring their survival in these harsh and unfamiliar lands.

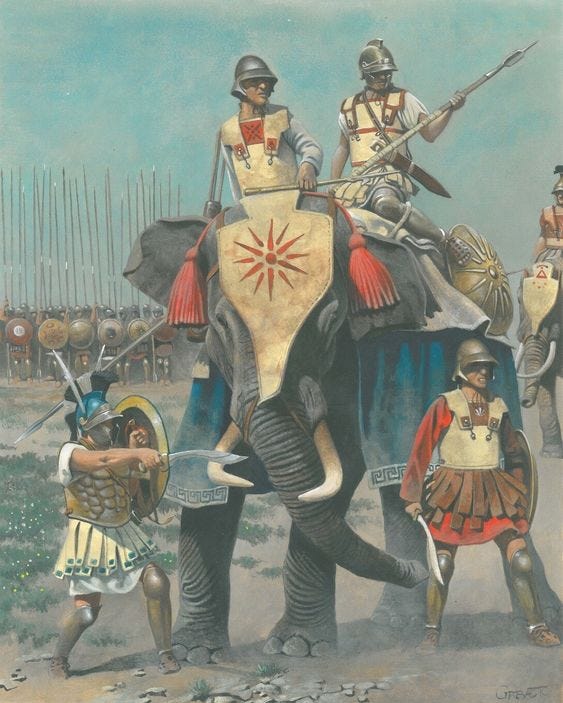

At that time, the Chinese state under the Han dynasty waged wars with the Huns. Chinese historian Ban Gu wrote that in 36 BC two chiefs, Gan Janszou and Chen Tang, commanding troops in the west (now Xinjiang and part of Central Asia), led a 40.000 army against the Huns, occupying the area around the city of Zhizhi (now in Kazakhstan).

Astonished Chinese warriors saw that the city was fortified with wooden palisades, fortified by powerful trunks. In Central Asia, the Huns did not know such a technique of building fortresses, but it is characteristic of the Roman martial art.

In the battle of Zhizhi, some tactics – never employed before - were deployed; some detachments combined their shields so closely that they resembled “fish scales”. This is similar to the famous Roman war formation called the “turtle” (testudo). The turtle’s troop was shielded by overlapping shields from all sides, including from above.

Despite the support of legionaries known for their bravery, the Huns suffered defeat. The Han Dynasty army took 1.500 prisoners, among which were 150 Romans, former soldiers of Crassus. Emperor Juandi ordered the Romans to settle in the Fanmu district and founded a city called Liqian for them.

In China, these Romans would have been a curiosity, with their Latin language, Roman customs, and advanced military tactics. Over generations, they would have assimilated into Chinese society, intermarrying with the local population and adopting Chinese customs. However, traces of their Roman heritage may have persisted, visible in certain military practices, architectural styles, or even physical features passed down through generations.

In the 1990s Chinese archaeologists were surprised to find the remains of an ancient fortification in Liqian that appeared strikingly similar to Roman defensive structures, sparkling the imagination of many. The 2005 DNA test results confirmed some of the villagers were indeed of Caucasian origin, leading many to conclude their descent from an ancient Roman army, although others remained less certain.

It needs to be mentioned that even though we are trying to assemble the loose pieces of a long-forgotten puzzle, there are gaps in this theory, which adds to the mystery. There were Greek Kingdoms deep into Asia long before the Romans ended up there; those cities eventually fell and those populations migrated or enslaved and lost in the steppes. Many clusters of populations in Afghanistan and the general Caucasus area claim to be descendants of the Greeks that conquered those lands thousands of years ago.

Also, Rome did not let this go; this defeat and the disappearance of so many Romans created a true nightmare for them; Cessar, just before he was assassinated, was planning on destroying Parthia for what they had done. Later, his successor Octavian – the first Emperor – negotiated with the Parthians asking for prisoner exchange. The Parthians replied there were no Roman prisoners.

The story of the lost Roman legion in China, while not definitively proven, represents a fascinating intersection of some of the ancient world's greatest civilizations. It is a tale of survival, adaptation, and the blending of cultures across vast distances.

Whether or not the legend is true, it highlights the far-reaching consequences of the Battle of Carrhae and the enduring mystery of what became of the Roman soldiers who survived that fateful day.

We talked about the "Roman Chinese" and the legend that surrounds them, but what about the Greek Afghans and Pakistanis? In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, which included the territory of modern-day Afghanistan. He established several cities in the region, including Alexandria Arachosia (modern-day Kandahar) and Alexandria on the Oxus (likely in modern-day northern Afghanistan). These cities became centers of Hellenistic culture and attracted settlers from Greece.

After Alexander's death, his empire fragmented, and the Seleucid Empire initially controlled the region. However, around 250 BCE, the region of Bactria (in northern Afghanistan and parts of Central Asia) gained independence under Diodotus I, establishing the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. This kingdom was a fusion of Greek and local cultures and was known for its wealth and Hellenistic influence, which persisted for several centuries.

Following the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, the Indo-Greek Kingdom emerged when Demetrius I of Bactria expanded into northern India around 180 BCE. The Indo-Greek rulers controlled large parts of Afghanistan and northern India, with their influence reaching as far as the Punjab region. This kingdom further solidified the Greek presence and cultural influence in the area.

Over time, the Greek settlers in Afghanistan and surrounding regions integrated with the local populations. They intermarried with locals, adopted local customs, and contributed to a unique Greco-Buddhist culture. Greek influence is evident in the art, architecture, and coinage of the region, with notable examples like the Gandhara art, which blended Greek artistic styles with Buddhist themes.

Some communities in Afghanistan, particularly in regions like Nuristan and the Wakhan Corridor, claim descent from ancient Greeks. While these claims are largely based on oral traditions, there are instances of physical features, such as lighter skin, blue or green eyes, and certain facial structures, which some speculate could be linked to ancient Greek ancestry.

In Afghanistan, a few modern tribes and communities claim Greek heritage, with these claims often rooted in local traditions and physical characteristics that differ from surrounding populations. These communities are primarily found in more isolated and mountainous regions, which historically have been less influenced by later waves of migration and conquest.

1. Nuristanis

Location: Nuristan province in eastern Afghanistan.

Claim to Greek Heritage: The Nuristanis, formerly known as Kafirs ("unbelievers") before their conversion to Islam in the late 19th century, are among the most well-known groups claiming descent from ancient Greeks. They inhabit a remote and mountainous region that was historically difficult for outside powers to control.

Characteristics: Nuristanis are often noted for their lighter skin, lighter hair, and blue or green eyes, physical traits that some have speculated might be linked to ancient Greek ancestry. While these characteristics can also be found in other populations in the region, the isolation of the Nuristanis has helped preserve these traits.

Cultural Legacy: The Nuristanis were known for their distinct pre-Islamic culture, which included unique religious practices and social structures. Some of their customs and rituals have been speculated to have possible Hellenistic influences, though this is debated among scholars.

2. The Kalash (in Pakistan)

Location: Chitral district in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan, near the Afghan border.

Claim to Greek Heritage: Although the Kalash are primarily found in Pakistan rather than Afghanistan, their proximity and similar claims are worth noting. The Kalash people have a rich oral tradition claiming descent from soldiers of Alexander the Great's army.

Characteristics: The Kalash are known for their distinct cultural practices, polytheistic religion, and physical features that differ from surrounding populations, including fair skin and light-colored eyes.

Cultural Legacy: The Kalash maintain a unique cultural identity with festivals, dress, and religious practices that are unlike those of the Muslim-majority regions surrounding them. Their claim to Greek ancestry is a central part of their identity, though it is more symbolic than proven by historical evidence.

3. The Pashtuns (select groups)

Location: Various regions in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Claim to Greek Heritage: Some sub-groups within the Pashtun tribes, particularly in the more remote areas, have traditions that claim descent from Greek settlers. These claims are less well-documented and more symbolic, with less emphasis on direct lineage and more on cultural memory.

Characteristics: The Pashtuns generally have a wide variety of physical appearances due to their diverse origins. Some Pashtun tribes have lighter features, which they occasionally link to ancient Greek or even broader Indo-European ancestry.

Cultural Legacy: While the Pashtuns have a complex and diverse cultural heritage, with influences from various waves of invaders and settlers, their claim to Greek ancestry is less prominent and more intertwined with broader regional histories.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to TheBlackWolf’s Lair to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.