Rome’s power depended upon its infantry and legions; until it was not enough.

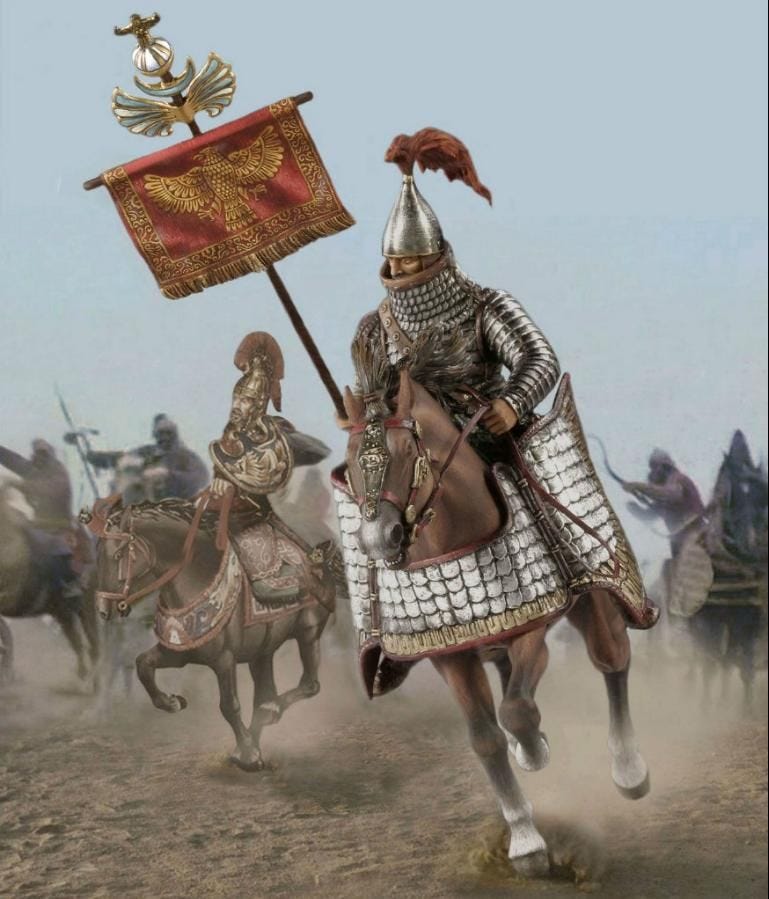

This is when the tanks of that period entered the fray; clad in shimmering scales, wielding lance and maces, they put the fear of God into the enemies of the Empire.

Enter the iron horsemen, Cataphracts!

Beneath the blazing Anatolian skies, the earth trembled. A wall of iron and flesh surged forward, lances gleaming, scales clinking in grim harmony. Byzantine cataphracts, elite shock troops, were no mere cavalry—they were the tanks of the era, forged from the disciplined might of Rome, the mobility Greece’s Companion Cavalry, and the crucible of a new era.

As their hooves thundered and enemy lines shattered, these armored horsemen stood as a bridge between worlds, the culmination of ancient warfare and the progenitor of the medieval knight.

The cataphract’s story begins with Rome, an empire built on the iron tread of its legions.

By the 3rd century, however, the world had changed. Barbarian horsemen and Persian cavalry exposed the limits of infantry, prompting emperors like Diocletian and Constantine to reform the Roman army. From this crucible emerged the clibanarii and cataphractarii, heavy cavalry inspired by the armored lancers of Parthia and Sassanid Persia.

When the Western Empire fell, the East—now the Byzantine Empire—carried this torch. By the 6th century, under Justinian, cataphracts became the empire’s mailed fist. The Strategikon, a military manual attributed to Emperor Maurice, describes them as versatile elites, trained to wield lance, sword, and bow with equal skill.

They were Rome’s answer to a mobile, chaotic world, preserving the empire’s logistical genius while embracing the cavalry’s future. In battles like Taginae (552), where the G of generals, Belisarius, crushed the Ostrogoths, cataphracts proved their worth, charging in disciplined wedges to break enemy resolve.

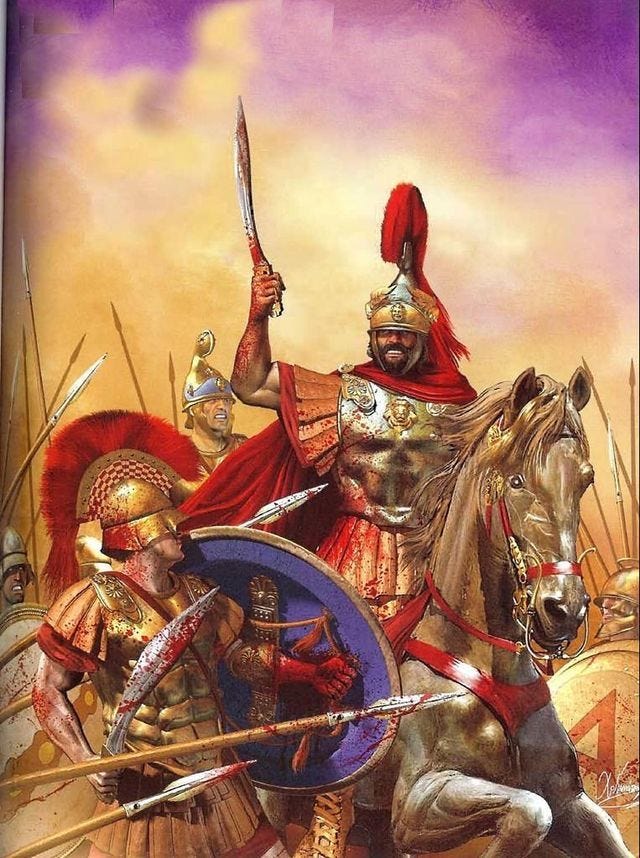

Yet the cataphract’s lineage stretches further back, to the sunlit plains of Northern Greece, in Macedonia. In the 4th century BC, Philip II and Alexander the Great evolved the Hellenic style of warfare and unleashed the Companion Cavalry, an aristocratic force of lance-wielding horsemen.

Clad in bronze and wielding the xyston, a long spear, the Companions smashed infantry lines in wedge formations, their charges at Chaeronea (338 BC) and Gaugamela (331 BC) rewriting the art of war. Their elite status and shock tactics left an indelible mark on the Hellenistic world.

As Alexander’s empire splintered, the Seleucids and Parthians blended Greek cavalry traditions with Eastern heavy armor, birthing early cataphracts. These ideas filtered into Rome’s eastern provinces, where the Byzantine Empire, Greek in language and culture, inherited them.

The cataphract’s kontarion, a 3–4-meter lance, echoed the Companion’s xyston, while their disciplined charges recalled Macedonian precision. In Byzantine society, cataphracts were often aristocrats, their prestige mirroring the Companions’ noble ethos.

They were, in truth, children of Greece, reborn in iron scales to guard a new Rome. They even had units of “Archontopoula” which means “noble children” in Greek.

The Archontopoula were indeed a real Byzantine military unit, established by Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118) during his military reforms in the late 11th century. Formed around 1090, amid wars against the Pechenegs and following the catastrophic losses at Manzikert (1071), they were an elite cavalry unit of approximately 2,000 men. Recruited from the orphans of Byzantine officers killed in battle, these “sons of the archons” were trained and equipped by the emperor, creating a loyal, disciplined force.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to TheBlackWolf’s Lair to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.